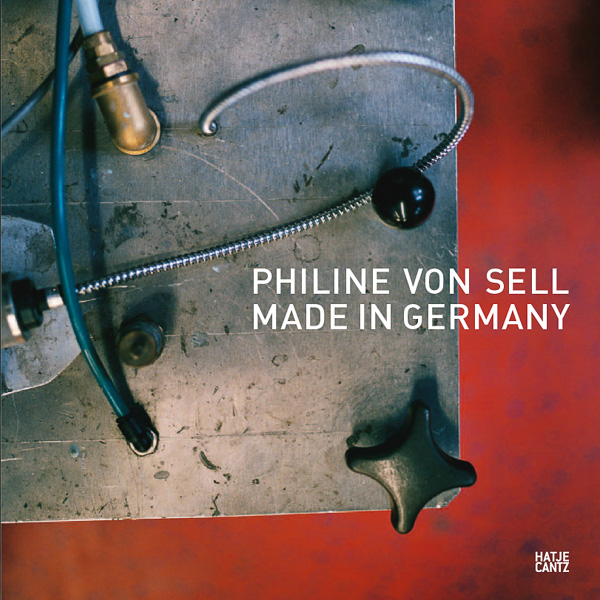

Exhibition Catalogue/Coffee Table Book

“…Philine von Sell reminds the viewer of the identity-endowing beauty of objects in daily life, just as she, free of didacticism, urges industry to be conscious of the aesthetic power of its products. The connection between sensuousness and understanding could not be more appealing.”…

Publisher: Hatje Cantz Verlag, Germany;108 pages, 70 colour illustrations, German/English; ISBN 978-3-7757-2198-1

Open the book here!

CURATORS AND ART HISTORIANS offer their interpretations of Philine von Sell’s photographs in three insightful essays.

“I use the medium of photography because my work methods and processes involve the potential in the blink of an eye,” says Philine von Sell. These fragmentary moments, lasting only split seconds, are created in von Sell’s images and stories. They incandesce with the vehemence of her sensual power, till in the end they signify exactly the opposite of the selfdissipating blink of an eye. They give rise to intermixing exterior and interior vision, to views and to insights.

The works of Philine von Sell thus unite the documentation of coincidence with the association of the essential, the objective ready made with the subjective reconception. In this way, her photo graphs of German factories and manufacturing sites, their products and their assembly processes, their daily routines and standardized gestures, become images with an aesthetic all their own, as unique as a fingerprint. This is also reflected in the photographer’s formal approach: von Sell selects a subject, shoots it without a tripod and with an analog mediumformat camera, uses only avail able light, and makes no later manipulations of any kind. The handmade print shows solely the artist’s respect for what she and her camera have, in the finest sense of the word, captured. The finesse of this approach and the timeless, almost classical vocabulary correspond to the high quality of the products that von Sell examines in the photographs presented here.

The proximity and appropriation described above give this artistic project a sociopolitical relevance, and for this reason the KonradAdenauerStiftung, founded in part with the aim of promoting art and culture, has engaged with it: Philine von Sell documents and shapes what lies hidden in the term creat-ing value, which has long since been reduced to its pecuniary aspect: namely, the accumu lating and precious added value that ex ists beyond all measurabi lity. The recognition of a moment of emotional quality that also emerges from and is signaled by a very much aesthetically based cultural memory: these images are about individual—and ultimately perhaps also collective—identity. Who does not remember the feel of a FaberCastell col ored pencil in the hand, the texture of its contours and the painted knob at the top? These memories are free of any consumeroriented superficiality. On the contrary: they reveal the magic of the perfect surface, manifested as a part of the in dividual’s own inner life.

Many production sites in Germany make things that contribute decisively to our cultural formation and education, and that have become a part of our lives. These products have become as natural and casual as Philine von Sell’s photos — and equally lasting. Paging through this book is thus a journey of discovery. It is an exciting journey in which the mixture of naturalistic and alienating vision makes unmistakably clear that the subject matter, for the most part devoid of human presence, does nothing other than refer ceaselessly to humans (and thereby to us as well). These works are about tracing our his to ry through companies that have rich tradi tions; the works have nothing to do with a mythically fraught exaggeration of commissioned photo graphy. The incorruptible artistic eye of Philine von Sell is selfconfident; and we rediscover our own selfconfi dence in this play between nearness and distance, auster ity and sympathy.

The Konrad AdenauerStiftung is pleased to take part in a project that possesses artistic quality and sociopolitical expressiveness in equal measure. Philine von Sell reminds the viewer of the identityendowing beauty of objects in daily life, just as she, free of didacticism, urges industry to be conscious of the aes thetic power of its products. The connection between sensuous ness and understanding could not be more appealing.

The palette is covered with dark and viscous gold, brushes and scrapers are accurately lined up. A hand, presumably a woman’s hand, assiduously and regulary dips the brush into the paint, as it might have done for years before. She is applying the dark red color, the liquid gold, onto plates and cups with virtous strokes. We suspect a repetitive act, but it seems harmonious and—contrary to the theses of the devoidness of meaning of the worker’s gestures —meaningful. Philine von Sell conveys the dignity of work, even if the worker cannot be seen in the image.

This has nothing to do with a romanticization of the worker. The choice of subjects and the style of the photographs do not prettify away the fact that this is manufacturing, where objects used in daily life are still produced with knowhow, by hand. Only a small number of people are on the immense factory floors, where machines clatter and clang, metal strikes against metal, rubber belts squeak, and cars, forklift trucks, and other vehicles drive, slightly overladen, across the polished com position floor. Now and then a hissing interrupts the torturous din, as though the escaping steam wished to call to mind the first hours of the Industrial Revolution, when steampowered monstro sities in gigantic factory spaces performed a symphony of cacophonous horror.

A lot of time has passed since then. The worker at the machine today enjoys much more protection from noise, toxic substances, and destructive work processes, and is seldom to be found in factory buildings at all, at least in socalled Old Europe. Insofar as people are regarded as a quantifiable cost factor, minimizing their presence has become economically valuable. This was already apparent to John Ruskin, the English art historian and social philosopher of early industrialization. In his maxims against the increasing erosion of meaning in English factory work, Ruskin developed an anthropocentric economic ethics that sought to identify the creative element or value in artisanal labor. For Ruskin, factories with functionally efficient designs were themselves synonyms for the decline in quality of human labor and its reception.

In his Book of Disquiet, the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa observes that things have only as much value as people attach to them. In the era of the paradigm shift from mechanical Modernism to the digital Postmodern, this is an almost exemplary dictum: that “good form” is still something solid and tangible. In other words, design in the ephemeral space of digital, no longer tangible form is not relieved of the responsibility of creating objects for people.

At the beginning of the twentyfirst century, globalized pro cess es of development and manufacturing have “liberated” objects from systems of national branding, indeed from seals of ap proval altogether. And in so doing these processes have also taken away any innocence the objects may have had as arti facts of erstwhile good form, deeply rooted in a sort of “social sculpture.”

Viewed in this way, the assembly sites that Philine von Sell visited in Germany must seem like anachronisms, relics of a time in which work went from hand to hand. Accordingly, the artist has photographed the products portrayed here—there is the temptation to call them, in the literal sense, manufac tures— “by hand,” with an analog sort of care, and has not digitally manipulated them in any way.

FaberCastell, Würth, Schleich, Rectus, Falke, Villeroy & Boch, or Dr. Oetker and all the other firms depicted are synonyms for just this Made in Germany, for entrepreneurial meticulousness and social responsibility. Originally it was the English who wished to protect domestic production; the Merchandise Marks Act of 1887 was intended to warn consumers against goods and products made in Germany. What was intended to restrict the flow of goods into England, however, turned out to succeed at doing the reverse. A growing number of German prod ucts proved to be of higher quality than the competition. It should be noted that many German industrial and artisanal techniques had been adopted from those used in England, the market leader of the time, though these techniques were then improved and refined, not least through the contributions of the schools of arts and crafts, and later, in many cases, the schools of applied art. Thus a stigma was transformed into a mark of distinction. What had been merely a statement of national origin became a seal of quality in manufacturing and production. “It was ultimately a matter of indifference wether it guaranteed quality because it was German or wether it was German be cause it guaranteed quality.”1

The work processes photographed here are expressions of industrial mass culture, and stand for serial production and auto matization. And yet the human factor is always present. FaberCastell leads continue to be sorted by hand. The modular paste at Eternit must be spread by hand onto the basic forms, which fit together endlessly. Bausch Decor produces decor paper that reproduces wood grain with striking verisimilitude. Before the unvarying pattern can be printed with unvarying intensity on enormous rolls, a worker must mix and prepare the paints, finding and recognizing the combinations that will result in an endless loop of the unvarying likeness of a given wood grain. As with French champagne, a highly regarded namebrand producer is always compelled to produce a sameness in taste.

The simulation is perfect. The endless repetition of events and processes—the mechanics—produce the object that is al ways the same. Perfection mutates from the artisanal excellence of seeking to create something singular to creating in defi nite constancy. The aesthetics of machine construction are oriented solely on the efficiency of its output.

Wolfgang Ruppert believes it is crucial to view the history of objects in a more open way, free of toonarrow concepts centered around the artifact. In his “Plea for the Concept of Industrial Mass Culture,”2 he remarks on the changes in perception that have taken place since the 1980s, and on a new openmindedness in the visual reception of the world of objects. In recent years, the aesthetics of the serial have almost play fully leaped across every boundary. The idea of a perfect reality, a world without flaws played at by the machines on factory floors, carryi ng out always uniform production processes with ceaselessly repeated sounds, shows, in a perhaps startling fashion, that almost no time has passed, aesthetically speaking, since Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927. Certainly our consciousness has changed fundamentally since the beginning of the age of technological reproducibility. Even so, we are haunted by the fascination of the constant. We quest soulfully after the singular, the error, exactly in that place where flawlessness is the mea s ure of all things.

Made in Germany is anachronism and zeitgeist rolled into one. The occasional dwelling mound may be built up, as it were, by hand, yet the brave new world of goods in the twentyfirst century remains a sort of floodplain, washed over by the ocean of world markets. And this is why we long for a point of refer ence, such as “good form,” to serve as a substantial signpost to No-Place: Utopia.

1 Rainer Metzger, “Exemplary Ground—On the Logic of the Label

‘Made in Germany’ in Contemporary Art,” in Made in Germany, exh. cat. kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, Kunstverein Hannover, Sprengel Museum Hannover (Ostfildern, 2007), p. 38.

2 Wolfgang Ruppert, “Plädoyer für den Begriff der industriellen Massenkultur,” in ibidem, ed., Lebensgeschichten. Zur deutschen Sozial geschichte 1850–1950 (Opladen, 1980), p. 153.

Philine von Sell’s photography project Made in Germany depicts moments, situations, and impressions of the world of labor in German industry. The artist sought out ten renowned German firms and visited their production sites, all over the country. Her photographs show manufacturing and production processes from a dispassionate perspective that recognizes the essential and the exceptional in the seemingly normal and routinized.

The project includes works created between 2006 and 2008 that depict mechanized and manual labor, as well as the onsite transformation of raw material into final product. All of this results from the artistphotographer’s perception and acti vity, unfolding and carefully examining an object of inquiry. The photo graphs in this volume are taken with a 4.5 x 6 cm mediumformat Pentax camera. The project is not finished, and Philine von Sell has plans to continue with it.

Made in Germany emphasizes the documentary aspects of viewing the modern reality of production. This series gives an observer the impression that the photographer discovered in the world of labor a succession of new and utterly surprising perspectives. It seems that a world opened up to the artist, one that amazed her with its complexity, precision, and efficiency. The photographer’s works present the very different production realities that she experienced—to which she devoted her own fresh gaze, in the form of a vision that shows great respect for the processes of labor and manufacturing.

The photographs show the specific characteristics of each industrial operation. In the manufacture of goods as various as ceramics, screws, and food products, it is clear that both raw materials and their processing will exert an in fluence over the immediate environment. The production sites of Dr. Oetker, Bausch Decor, Falke, Rectus, Würth, Eternit, the banknote printers Giesecke & Devrient, and other leading German companies are characterized both by the materials they use and by the technological and artisanal demands of the production, sort ing, and storage of their highquality goods. In this way, each firm possesses something exceptional, something unmistakably its own. Each manufacturing process, work bench, and workplace has something distinctive, as does each organizational system (or lack thereof), and, needless to say, each production site’s archi tecture.

The photographs that Philine von Sell produced for Made in Germany are as various as the products and their manufac turing. This is because she immersed herself in a new situation at each new firm, developing an appropriate form of viewing for each new situation: For example, the photograph entitled Zahlen (Numbers), made in a Villeroy & Boch factory (ill. p. 87), shows ceramic products arranged in pallets awaiting finishing. This photograph presents interim storage as an organizatio nal process: the composition is a frontal view, with a balance be tween the horizontal and the vertical that emphasizes the serial aspect of manufacturing. In contrast to the production of colored pencils, for example, the objects here stand in rank and file, set apart from one another by precise, repeating distances. In addition, the production process dictates that the batches be labeled with reference numbers comprehensible only to the “initiated.”

A brief look back: in the years since the mid1920s, modern photography has often been concerned with photographing and conceptualizing the world of industry and production. Industrial photography, industrial reportage, and socalled objective and material photography allowed for dramatic new insights into the modern world, into its technological reality and its productive specificity. Albert RengerPatzsch (1897–1966) gained prominence through his photography and photo books, such as the volume Die Welt ist schön (The World Is Beautiful, 1928), in which he displayed structural similarities between nature and modern technology and parallels between biologically evolved and technologically constructed reality. RengerPatzsch did not regard photography as an art. Instead, he spoke in his theoretical writings of “photographic handicraft” and argued for the unity of method and means. His “objective photographs,” drawn from his ideas on the tasks of the medium, were revolutionary within the emerging field of “artistic photography.”1

Certain of Philine von Sell’s images seem to occupy a borderland between the real and the surreal, in particular those works that evoke conceptions that go beyond the actual product. Among this group is a photo shot from above showing the surface of a red table, atop which is a metal bucket bearing traces of green pigment (ill. p. 42). The bucket is a tool used at FaberCastell to scoop pigment out of bins. Against the deep red background of the tabletop, the subject appears as a form that has been utterly reduced—like an idol from another culture, or a modern sculpture.

Such observations bear witness to the artist’s precise percep tion of reality, which she uses to discover exceptional things in the everyday. This approach to photography is ulti mate ly also the reason why Philine von Sell only infrequently shows people at work: her main interest lies in the broader context, the atmos phere of the factories. Though people rarely enter into such images of production, the photos often contain traces of their existence and activities. Philine von Sell shows the forms and objects that workers produce, and the sites that they affect. Yet she does so only as an exception, much as labor by hand is the exception rather than the rule. Von Sell is not interested in portraits, faces, gestures, or attitudes at work, but rather in the depiction of contexts of work, and in the technological and organizational conditions of factories. Her photography corresponds to the reality of work today. Humans are still irreplaceable, since it is not yet close to possible to replace human ability, intelligence, and fine motor skills with machines; yet the number of humans required for a given quantity of production is lower now than at any prior epoch in history. Though humans are still eminently important for production, they have in fact become an ephemeral quantity—which is reflected in Made in Germany. On the other hand, when work ers do appear, in a small number of photographs, they are at the center of the action, with the photographer presenting the interplay of their activities with machines and objects. The potter’s wheels at Villeroy & Boch stand empty, yet it is clear that creative artisanal work is done at these workstations.

What is more, the clear and balanced tectonics of von Sell’s photographs speak in a clear language, and define the quality of her images. Her compositions bring into view organizational concepts and work systems that are indispensable for the achievement of the high daily standard of production worthy of the seal “Made in Germany.” “It is not only a matter of high performance, but of high performance sustained—of guaranteeing permanen tly high performance and quality. That is something exceptional—and that is what I associate with the term ‘Made in Germany,’” says von Sell. She goes on: “Everything has a soul—not only people, but things, too, have their honor.” Indeed, this formulation may have been fundamental to Made in Germany, but in today’s globalized industry modern design concepts that emphasize the ongoing development and improvement of production and of products are most important. Design involves goods and their prices. Functionality and functioning are key, and it is precisely these aspects that are two of the great strengths of German industrial goods. The artistic gaze transforms this fact through subjective observation—which seems necessary to get a look into contemporary industrial activities at all; after all, as consumers we are familiar with goods, but not very familiar with how they are produced.

But it is also true that the boundaries between design and art are now being erased, such that areas of overlap exist between the two realms. This does not necessarily mean that our entire reality has been artistically shaped. There may be, however, a stillhidden issue here for Modernism and its succes sors, an issue not yet fully grasped, still halfconscious. Only time will tell us more. It may be that one of the last, if one of the greatest, utopias is illuminating our path out of the Modernism of the twentieth century into the present. To have recognized this methodologically, and to have realized it through photography, is the achievement of Philine von Sell, who has made her personal way of seeing the point of departure for the major inquiry that is Made in Germany.

1 Ingeborg Güssow, “Die neusachliche Photographie,” in Kunst und Technik in den 20er Jahren. Neue Sachlichkeit und gegenständ licher Konstruktivismus, exh. cat. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus

(Munich, 1980), pp. 97–98.